Flaxseeds have been trending for a while now. But did you know that this powerhouse of nutrients was part of the traditional Indian diet? Read on to discover a delicious and nutritious flaxseed recipe as well as the nourishing role these seeds have in the Himālayas.

What are Alsī Laḍḍūs?

I can’t get enough of alsī laḍḍūs, or fantastic flax balls as I have come to call them. Making these nutty, slightly sweet, munchable treats during the frigid months is becoming a family tradition.

Last winter, my khākho (mother-in-law) asked me to pick up “alsī” as I made the weekly grocery trek to the market. This was a completely new term to me.

During my first attempt to get alsī, I made two mistakes. First, I didn’t check online to see what “alsī” means in English, and second, I didn’t clarify whether these were seeds my MIL wanted for cooking, rather than planting. At the general store my general confusion caused a mire of miscommunication. I came back empty handed.

Before my second attempt, I found out to my delight that “alsī” means “flax.” Armed with a new enthusiasm to secure a long-missed superfood, and a picture on my phone just in case, I was able to get a few kilos of flaxseed from the market along with the other ingredients to make this healthy take on laḍḍū, a beloved Indian sweetmeat.

Despite a decade of living in India, I had no idea that people here ate flaxseed. Continue reading to learn a bit more about the traditional role of flax in India as wells as Gaddī wisdom concerning the best time to eat it. If you’re just here to nom nom, jump ahead to the recipe.

Flaxseed in India

I don’t mean to throw shade, but as a health-conscious Californian who had grown up eating Caribbean takes on Indian food, my first experiences of food in North India were lackluster. At every corner you find overcooked vegetables, oily snacks, and intensely sweet sweets.

Now that I’m living a rural setting where the diet is slightly less impacted by modernity, I’m discovering far more appealing and nutrient dense dining options. The traditional seed queen of India, Vandana Shiva, hasn’t commented specifically on flaxseed, but I think it’s a forgotten food source that she would get behind, in a similar way to reviving millets.

Flax goes a long way back, no matter where you’re looking. Research suggests that flax was first domesticated around 8,000 BCE in the Fertile Crescent. It has been cultivated in India for approximately 5,000 years and is known by many different regional names like Tisi (Bengali), Ali Vidai (Tamil), and Jawas (Marathi).

This means that in addition to the alsī laḍḍus of Himāchal, you can find other regional takes on flaxseed like this spiced powder to accompany idlis and dosas as well as crisp and aromatic Gujarati khakhras (crackers).

Feel the Heat

A pervasive assessment of food found throughout Asia is whether food is “hot” or “cold” – though this has nothing to do with the physical temperature. The modern Indian view of nutrition is heavily influenced by Ayurveda, which assesses the qualities of bodies as well as foods according to a triadic system of the tridoṣha – vātā (windy), pitta (fiery), kapha (watery/earthy).

Thinking in terms of the simplified hot/cold duality prevails in the popular imagination. I have lost count of times where someone has refused to eat “x” because it is “hot/cold” and would therefore be inappropriate for the season or a particular malady that they have.

This is important for understanding why people make and eat alsī laḍḍūs when they do. Alsī/flax is considered very “hot.” Hence, the appropriate time to eat them is when it is very cold outside. Interestingly, bundles of flax seeds have been used in hot compresses and poultices in Western herbalism because of how well the seeds retain heat.

Gaddī Take on Wellness

I asked my khākho where she leaned to make alsī laḍḍūs from and she said that her mother used to make them for her paternal grandmother (dādī) in the winters. My sister-in-law chimed in that her family makes them in winter too.

As we were hand-rolling the laḍḍū’s my khākho commented that the best time to eat alsī was “Magar Pañjī.” I stared blankly at her. All the years of living in Varanasi and observing dozens of new festivals didn’t help with any context. She tried to elaborate on what she meant, but I had to drag in a most reluctant translator– my husband.

Eventually I realized that Magar Pañjī refers to a specific seasonal time at the junction of Pauṣha and Māgha. The 12-month Hindu lunisolar calendar only approximately lines up with the Gregorian one. The depths of winter, usually regarded as January and February, correspond to the Hindu months of Pauṣha and Māgha. Specifically, Magar Pañjī is a 16 day period comprised of the last eight days of Pauṣha and the first eight days of Māgha.

We have a neighbor who is a pūjārī (ritual priest) and a bit more knowledgeable about these things. When I asked him about it, he confirmed a suspicion I had that “Magar” is a local version of “Makar”, which is a zodiac sign usually equated with Capricorn. The entrance of the sun into Makar is marked by a great festival called “Makar Sankrānti” which is observed every year on January 14th. Since the calendar months are determined by the moon, and not the sun, the timing of Magar Pañjī will change relative to Makar Sankrānti. “Pañjī” comes from the Sanskrit for “five,” “pañca.”

So Magar Pañjī literally means “5 days of Capricorn.” But wait, where did 16 days come from. Our neighbor explained that the main time is five days in Pauṣha and five days in Māgha. Three days have been added to each half of the period for reasons unknown.

In any case, Gaddīs believe that eating things like alsī laḍḍūs has its maximum benefit during this coldest time of the year. In addition to providing nourishing warmth to the body, it is said to reduce joint pain and promote overall vitality, with residual effects throughout the coming year.

When I prodded my khākho further about this Magar Pañjī, she said that people should generally eat things that are warm in nature. She also said that people don’t give salt to cows during this time as it will cause them to drink excessive water, which is cooling and might lead to other problems. The snow which falls during this time is said to be the best snow, which stays a long time, giving continuous water to the plants as it thaws and killing field mice trapped beneath it.

She went on to describe two other 16-day long periods of the year, one during the height of the hot season and the other during the gauntlet of the rainy season. I’m sure they each come with prescriptions for well-being which we can’t get into now.

I think it is interesting to see how the same foodstuff is seen as highly beneficial in different paradigms. Just in case you’re less familiar with flax, here’s a brief explainer from the modern, Western wellness perspective.

Flex your Flax: How to Process Flaxseeds for Optimal Nutrition

The reason many people, especially vegetarians, reach for flaxseed and its oil is the high concentration of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). This is an Omega-3 fatty acid similar to eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), both of which are common in seafood. Omega-3s are important for heart, circulatory, joint, and brain health. It’s important to note that our body can’t integrate ALA as efficiently as EPA and DHA.

Fortunately, ALA is only one of flax’s nutritional assets. Flaxseed is also high in macronutrients like protein and fiber as well as minerals like potassium and phosphorus. For a reliable breakdown of raw flaxseed’s nutritional information, see Table 1 of this study. Flaxseed is also high in lingans, a phytoestrogen (compound found in plants which mimics estrogen in the body) which has strong anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and potential anti-cancer properties.

To get the most out of flaxseeds, there are two important things to do.

1. Roast them

Even health food has its hang-ups. One fault in flax is the presence of linamarin, a phytotoxin whose metabolism can produce harmful components in the body. Luckily, it is not present in very high quantities and there is something you can do to neutralize it – roast your seeds!

Exposure to heat neutralizes linamarin and brings out an irresistibly nutty aroma, similar to roasted cashews. Not all people get behind roasting flaxseeds due to the belief that some of the nutritional benefits of raw seeds and oil are lost due to heating. This piece of research points out the nuance in how heat affects flaxseed’s protein profile and this article looks into the effect of heat on flaxseed oil.

For me, the jury is still out as far as roasting goes. There seem to be nutritional benefits to roasting (reducing phytotoxins) as well as detriments (denaturing proteins, oxidizing oils). Flavor-wise, roasting is a clear win. If you have any other insights or experience with consuming flax raw vs roasted, please leave a comment below!

2. Grind them

This is a more universally supported step. The shiny, wax-like outer sheath of flaxseed isn’t broken down by our digestive track. When you add whole flaxseeds to foods, only a small portion of them will be effectively chewed up by the teeth before making their way down. The rest of them make it all the way through unscathed and deny us their awesome power.

The surefire way to have access to all of the wholesome goodness of flaxseeds is to grind them before adding them to your food. Make sure you only grind a small amount at a time as they can spoil relatively quickly once their outer shell is compromised.

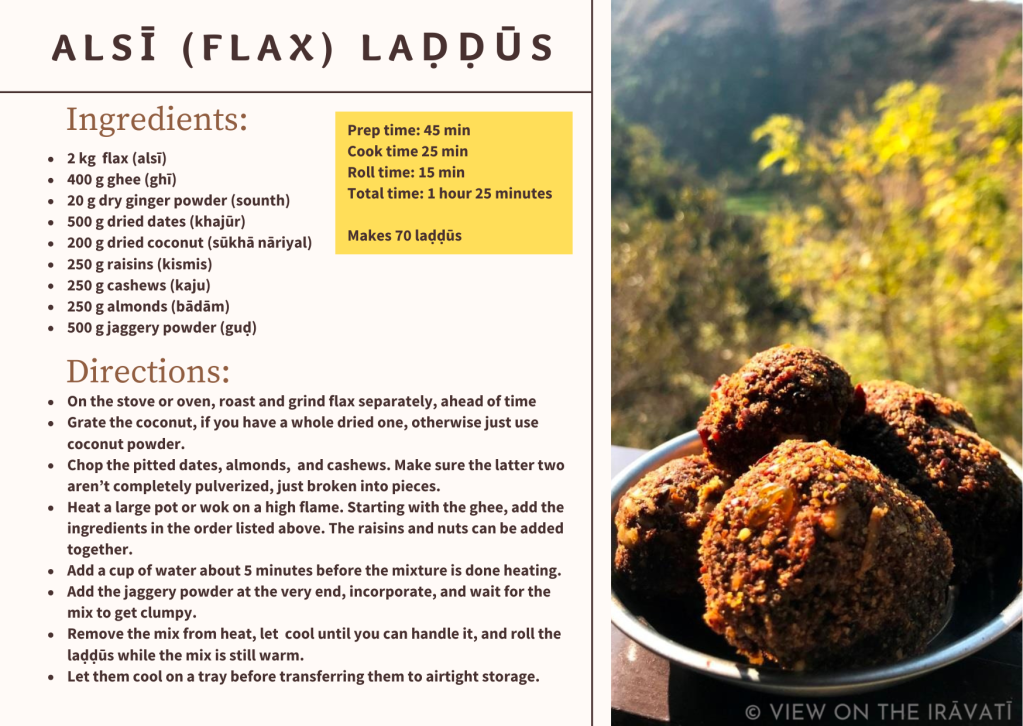

Making Alsī Laḍḍūs

Finally, we are sitting by the kitchen fire on a cold winter’s day preparing to make alsī laḍḍūs. My khākho has a stack of wood next to her and we have prepped all of the ingredients.

- 2 kg of flaxseed has been roasted, cooled, and ground (O, the foresight of traditional ways!)

- 250 g of almonds and 250 g of cashews have been pounded into little pieces

- a whole dried coconut has been grated (about 250-300 g)

- 250 g of very dry dates have been pitted and chopped

- 250g of golden raisins have been cleaned (dry) and set aside

- 500 g of jaggery (guḍ) has been ground to the consistency of brown sugar

We made these on an iron wood stove (chula) using a kaḍhai (thick wok) to roast all the ingredients. Roasting the flax seeds in an oven is another option. Here are some basic instructions for that. The rest of the ingredients could be roasted in a skillet on a stove top similarly to how I describe below.

First, we put a generous portion of ghee, about 400 grams, into the kaḍhai. The only spice we used in this version was a few tablespoons of dried and ground ginger, which we added first into the sizzling ghee.

Next we add the chopped dates, shredded coconut, and chopped nuts, stirring continuously to coat everything in the ghee and ginger mixture. A little later we add the whole raisins as well.

After everything has been roasted together, we incorporate the flaxseed meal handful by handful. Once it is mixed in with everything else and well-heated, we poured about 1.5 cups of water over the mixture and stir. This produces a very satisfying sizzle.

The last step in the heating part of the process is adding the ground jaggery shortly after the water has been added. They will work together as a binding agent. In case you’d really like to cut back on the ghee and sugar, you’re free to do so, but you won’t be able to roll laḍḍus and can instead enjoy this as a kind of trail mix.

Continue roasting the mixture until clumps start to form and they look shiny as the ghee and oils start to separate out. Next, we emptied the steaming hot contents of the kaḍhai onto a large dish. When everything has cooled enough to be handled, but is still warm, we set to work taking handfuls of the mix and squeezing, then rolling, them into balls of various sizes – big for us, small for the kids.

Shanu, my youngest niece who is five and has a sweet tooth for the ages, joined us at this point. Making a play on words between “alsī”(flax) and “ālsī” (lazy), she couldn’t stop joking about giving her “ālsī”(lazy) laḍḍūs.

Yet these laḍḍūs will make you anything but lazy! I’ve been enjoying them for a few days as an accompaniment to my morning coffee and can feel the sustained energy they give. I don’t start to crave any other food until well after noon.

Alsī Laḍḍū Recipe Card and Preparation Tips

Basic equipment you’ll need:

- Food processor/blender

- Large wok

- Large bowl or platter for emptying the hot laḍḍu mix on to

- Another platter or baking sheet for resting rolled laḍḍus before storage

- Oven and baking tray (optional)

Cooking Tips:

- A key part of the prep is roasting the large batch of flax seeds ahead of time, giving them enough time to cool, and grinding them. This could even be done a day ahead.

- Add ghee as needed while cooking

- Add about 1-2 cups water as cooking to soften flax and keep ingredients from burning.

- Be careful not to burn the mixture, the thicker the pan/wok/kaḍhai, the better.

- It is ready to roll once oil/ghee separates out a bit. You can always take a bit out and try to roll it and see if it binds to test. If it doesn’t, you can always add a little bit more water and jaggery as needed.

Here are a few extra notes, in case you’d like to try making these at home:

- This is a really fun recipe to make with a partner, friends, or kids who can resist the temptation to eat all the laḍḍū precursors. It will really cut down on the prep time and rolling time

- For this batch we had over 3 kg of raw ingredients, which produced about 70 laḍḍūs, and we made them in two rounds.

- For most people working in Western kitchens, with less munchers than in a joint family household, you might want to half the amounts listed.

- Looking at notes from last year, I noticed we made them slightly differently with 150 g of melon seeds and about 500g of sesame that replaced the same amount of flax. You could really go wild with any combination of dried fruits and nuts like: walnuts, pistachios, poppy seeds, dried figs, or apricots.

- I think cinnamon, cardamom, and/or nutmeg could also be nice additions to this recipe. For the truly adventurous, cacao powder is always an option.

- By local standards these laḍḍūs involve some pretty premium ingredients. I spent the equivalent of USD $30 on everything, which is more than we spend on a month’s supply of rice and lentils for a family of 10 (though staples are heavily subsidized by the government in Himāchal). I don’t want to imagine how expensive these must be to make in California! To make these more budget-friendly, it would be a good idea to get as many ingredients as you can from a Middle Eastern or Indian supermarket, or a place that sells bulk goods.

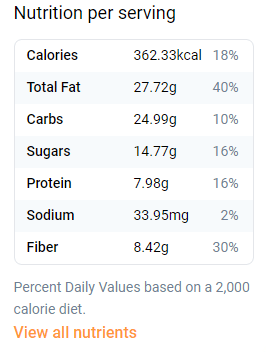

Nutritional Info

This is a breakdown of the macronutrients in alsī laḍḍūs generated by the Samsung Food app. A full ingredient list and “health score” are available here.

A serving is one laḍḍū. I don’t have a kitchen scale, so my rough estimate is that each laḍḍū weighs between 40 g and 50 g.

Some people might look at the calories per serving, especially the fat, and balk at calling this a “health food.” If the fat content truly offends you and you’d like to bring the nutritional profile closer to that of a Cliff Bar, consider incorporating whey or pea protein powder, or even roasted barley flour, as a filler to replace some of the nuts and seeds.

Since anything resembling a Cliff or granola bar is hard to come by out here, I’m grateful that my khākho has such a tasty and nourishing recipe up her sleeve. If you do get a chance to make them and have any feedback, suggestions, or if any steps of the recipe are unclear, let me know in the comments!

Leave a comment